| TOP > Our Roots - To Serve the Suffering Poor |

Founding spirit

‘Treat the patient, not the disease’

Explanation

The founding spirit, ‘Treat the patient, not the disease’, is a condensed version of the goal of our founder, Kanehiro Takaki, to ‘train doctors who have medical and human abilities’. This spirit is also incorporated into our nursing education as ‘Care for the patient, not the disease’.

The University’s contributions to society through our research and medical practice are also made with this spirit.

Founding Spirit - Patient-Centered Medical Care

Before going to England, Kanehiro Takaki had already received direct practical training in English medicine from the English physician William Willis (in Japan 1861 to 1881). Then, after studying for 5 years at St. Thomas's Hospital Medical School in London, he returned to Japan imbued with the spirit of English medicine. Takaki believed that medicine was "a practical knowledge; above all, it is for the prevention and treatment of illness." He put his beliefs into practice immediately upon his return to Japan by starting research on beriberi, which was generally believed at that time to be an infectious disease. Using two Imperial Japanese Navy training ships on long sea voyages, Takaki focused on dietary deficiency as the cause of beriberi and with this approach succeeded in completely eradicating beriberi from the Japanese navy. By doing so he also showed that theories, no matter how widely accepted, are useless unless they help patients.

Takaki Tests His Dietary Theory of Beriberi

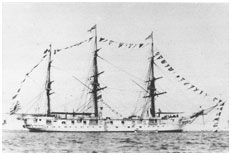

To test his dietary theory, Takaki gave the crew of the training ship, Ryujo a white-rice diet and gave the crew of another training ship, Tsukuba, an enriched diet of his own devising. Leaving Japan in December 1882 and in February 1884 RyuJo and Tsukuba sailed to New Zealand, along the coast of South America from Santiago to Lima, to Honolulu, and back to Japan in voyages lasting some 9 months. Of the 376 crewmen of Ryujo, all of whom were eating the white-rice diet, 161 contracted beriberi and 25 died. However, only 14 of the crew of Tsukuba, who ate Takaki's enriched diet, contracted beriberi and none died. This experiment was a victory for practical medicine based on a masterful blend of basic medical research and clinical medical practice. Takaki's success came 10 years before Dutch hygienist Christian Eijkman, working in the Dutch colony of Batavia (now Indonesia), advanced his theory that beriberi was caused by a nutritional deficiency. (Eijkman's later identification of the "anti-beriberi vitamin" in rice bran - vitamin B1 - won him, along with Sir Frederick G. Hopkins of England, the 1929 Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology).

The Beriberi Debate and English-Language Instruction

Despite Takaki's success in proving his dietary-deficiency theory, the "German school" of the University of Tokyo and the Army Medical Corps clung doggedly to their belief that beriberi was an infectious disease, giving rise to the famous "beriberi debate." This debate clearly manifested the fundamental conflict between the nava1 doctors with their preference for English medicine and the University of Tokyo and army doctors with their adherence to German medicine - a conflict that surfaced in many other matters. Takaki's choice of English (and rejection of German) as the foreign language to be taught at his medical school was another form of his opposition to the "German school."

|

|

| Tsukuba,a training ship of the Japanese navy |

|

Takaki's advocacy of practical medicine guided his selection of teachers for his medical college (Igaku Semmon Gakko), as is evident in the array of talent assembled: pathology professor Katsusaburo Yamagiwa, first in the world to succeed in experimental carcinogenesis; bacteriology professor Sahachiro Hata, first, with Paul Ehrlich, to succeed in producing the salvarsan compound for chemotherapy; and psychiatry professor Shoma Morita, originator of the famous "Morita psychotherapy," which rivals Freud's psychoanalytic method. Whereas many aspiring medical schools did not receive government approval, Takaki's Igaku Semmon Gakko was quickly approved in 1903 because of its superior faculty, facilities, and equipment. It was, in fact, the first private medical college in Japan. Typical of Takaki's emphasis on the practical in medical education was that his students were the first in Japan to dissect human cadavers.

As well as emphasizing practical medical education, Takaki was equally, or perhaps even more, concerned with education for developing the human character. A patient is not merely a bundle of cells and organs but a human being suffering from illness. The physician must have the "healer's heart" to sense and share that suffering. To cultivate such a "heart," Takaki explored many approaches. Lectures on Buddhist wisdom were one example. He himself had a deep interest in Zen and immersed himself in that world.

|

| Monument at the initial site of the Sei-I-Kwai Medical Training School(Ginza,Chuo-ku,Tokyo) |

|

What Takaki sought in his educational program was to "nurture in physicians both medical skills firmly rooted in medical knowledge and a compassionate heart." Indeed, caring for the entire person (holistic medicine) has always been the goal of the physician. In this spirit, The Jikei University regards the first one year and half of medical education as a crucial period for developing the human character.

Shortly after acquiring university status in 1921, our university was devastated by the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923) and the fires that followed. Most of the buildings and equipment were reduced to ashes. The president and his staff, however, turned to the painful process of rebuilding. Another setback was suffered in the early postwar period (1947) with the forced separation of Tokyo Jikeikai, its hospital, and the university from each other. The university was incorporated independently (The Jikei University). Tokyo Jikeikai formally "lent without compensation" the hospital to the university (i.e., the hospital became attached to the university). The Jikeikai itself focused exclusively on nurses' education.

Thus, despite several severe crises, the educational spirit of Takaki continues to thrive, nurtured and passed down from the founding of the Sei-I-Kwai to the present day.

Although space does not permit the listing of all the contributions of past presidents of the medical school, college, and university, we can at least symbolize our deep appreciation by listing their names and years of service.

Kanehiro Takaki (1881-1920)

Yasuzumi Saneyoshi (1920-1921)

Eigoro Kanasugi (1921-1942)

Yoshihiro Takaki (1942-1947)

Takeyoshi Nagayama (1947-1952)

Masanaka Terada (1952-1956)

Yoshio Yazaki (1956-1958)

Kazushige Higuchi (1958-1975)

Reiji Natori (1975-1982)

Masakazu Abe (1982-1992)

Tetsuo Okamura (1992-2000)

Satoshi Kurihara (2001-2013)

Senya Matsufuji (2013- )

Today(as of september 2021), The Jikei University is considered a leading private medical school, with over 13,000 medical and nursing graduates (Faculty of Medicine) since 1881.

|